Born or Naturalized in the USA: Citizenship in the Period of Chinese Exclusion

It’s been almost 140 years since October 22, 1884, when an 8-year-old named Mamie Tape walked to her first day of school at Spring Valley Elementary, one of the best public schools in California, in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in San Francisco. The night before, Mamie’s father, Joseph Tape, had tried to enroll her at Spring Valley, but his petition was denied by the San Francisco school board. The board insisted that Mamie – and “Mongolian child[ren]” like her – didn’t have the right to go to school because their parents were ineligible for naturalization.

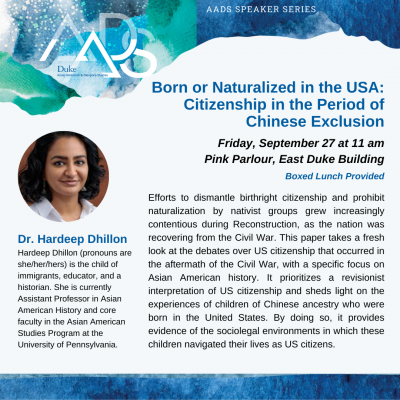

University of Pennsylvania Professor Hardeep Dhillon’s talk on September 27, “Born in the USA: Chinese American Children in the Period of Exclusion,” reanimated contemporary questions about the historical period of Chinese exclusion, but also added new dimensions to the bounds of racialized citizenship, education, and disenfranchisement. In the mid 19th century, thousands of Chinese immigrants left China looking for the so-called Gold Mountain. In many of the places they landed, they found themselves caught in a web of legal discrimination.

The struggle for the rights of Chinese people in the U.S. is inextricable from histories of enslavement and abolition. Broadly, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments theoretically abolished slavery, protected birthright citizenship, and extended voting protections to all men regardless of race. The enactment of these rights, of course, proved to be much more complicated. Only by continuing to exclude Chinese people from citizenship did the 15th Amendment pass in the first place, while Mamie Tape’s case, which eventually reached the Supreme Court, proved that birthright citizenship for all children had never been a given. Parents wrote to the San Francisco school board demanding either the creation of schools for Chinese kids or the inclusion of Chinese kids in existing education systems. An extended legal battle ensued, resulting in the opening of a new Chinese school, and providing new fire for politicians who based large portions of their platforms on sinophobic rhetoric.

Dr. Dhillon argued that there’s actually a deep connection between the rights of migrants in the interior of the U.S. and on the border, not just temporally, but also in the moves that nativists make to disenfranchise certain kids. In tandem with legal fights over the right of the Chinese child to American education, legal conflicts over deportation started flaring up after the Exclusion Act of 1882. Immigration inspectors kept detaining and deporting kids, forcing even those born in the U.S. to constantly prove their citizenship. Through a “revisionist history” of the Wong Kim Ark case, Dr. Dhillon traced the racist legal considerations that ended up securing birthright citizenship for all children. In January 1896, John Collins, a California lawyer at Hastings Law, wrote to the attorney general asking for a decision to be made before the election. Upending birthright citizenship would disenfranchise a lot of white citizens born to immigrant parents, he argued, and they would need time to get naturalized (something that, due to existing precedent, wasn’t an option for Chinese people). Citizenship status and voting status were thus tethered together, and even though these documents weren’t ever part of public discourse, they reiterated an argument made by lower courts: that the unequal application of the Fourteenth Amendment would exclude from citizenship children of English, Scotch, Irish, German, and other European descent. The case was eventually decided in favor of Wong Kim Ark, but questions of the rights of Chinese people born in the Americas remained ambivalent for long afterward, and their residues still shape our understandings of citizenship and legal protections today.

After the talk, Dr. Dhillon facilitated a Q&A session that spanned legal history, frameworks for thinking about Asian American Studies, and her own attachments to her research. As a child of immigrants, she explained, this work is personal for her. The shifting historical bounds of American-ness have deep, profound impacts for the contemporary racialization of citizenship. At UPenn, her scholarship focuses on the history of immigration to the U.S. and the legal practices that historically shaped immigrant lives. Recently, much of her work has been focused on children and the family, and the ways that legality impacted the formation of the modern family in the American context. The legal history of migration in the U.S., she maintained, is inextricable from the way that relational race formations have shaped the notions of nation, family, and citizen which we still hold today.